Year

2022

Introduction

More than a decade ago a group of earth system and environmental scientists published a paper to define nine planetary life support systems that are essential for human survival (Rockström et al. 2009). For each of these nine planetary life support systems the researchers defined a boundary within which humanity could thrive for the generations to come. In order to stay within these boundaries many societies, especially those with a high level of income, need to transform their habits and practices towards social-ecological resilience and sustainability (WBGU 2011). These societal transformation processes, whether they relate to changes of economic systems, urban infrastructures or consumer behaviors, are driven or prevented by individual and collective actions.

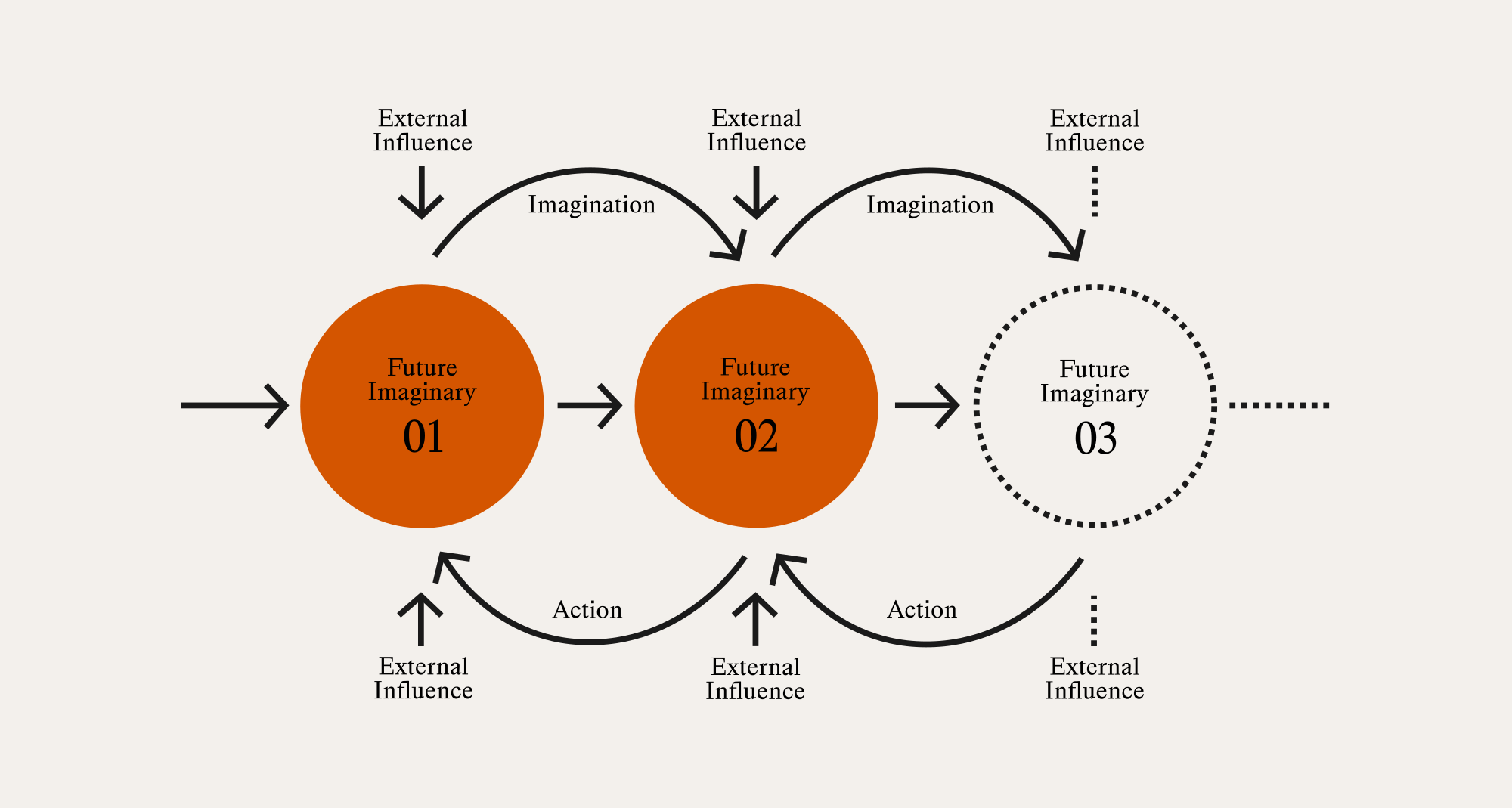

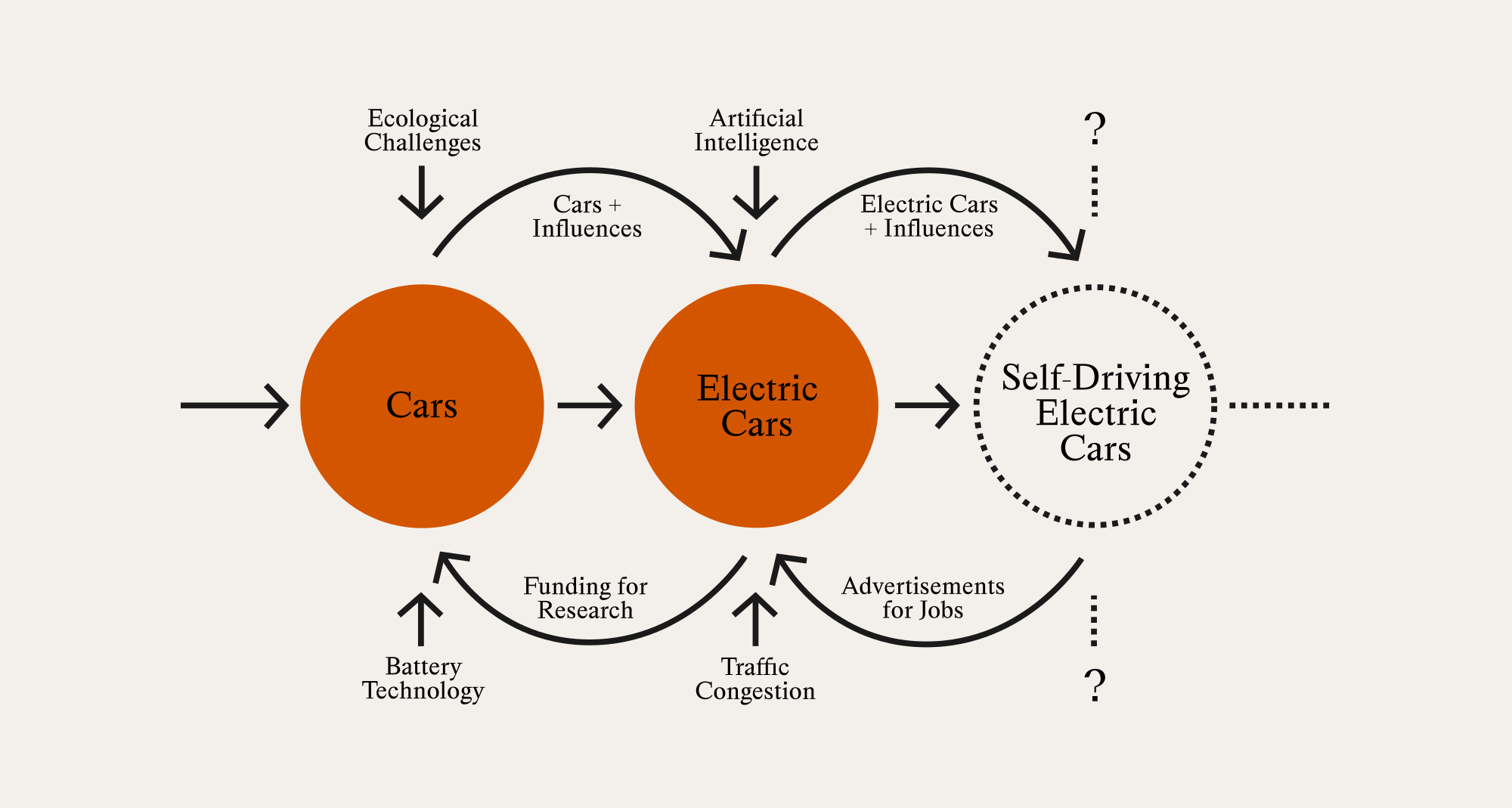

Though, people aren't completely free and act within social structures that contain imaginations like assumptions, norms and expectations (Esser 1999). Future imaginaries are such imaginations about the future that affect individual and collective actions in the present. As consequence these actions shape social structures and therefore future imaginaries. The following is an attempt to explain these causal effects between future imaginaries and the development of social structures. It will also be discussed why and how practices of unsustainability get reproduced through future imaginaries. Both aspects will be addressed by answering the questions how future imaginaries affect the actions of individuals and organizations, and how in turn these actions affect social structures, and therefore the further development of future imaginaries. To illustrate the developed conception, future imaginaries in the field of mobility will be used as an example.

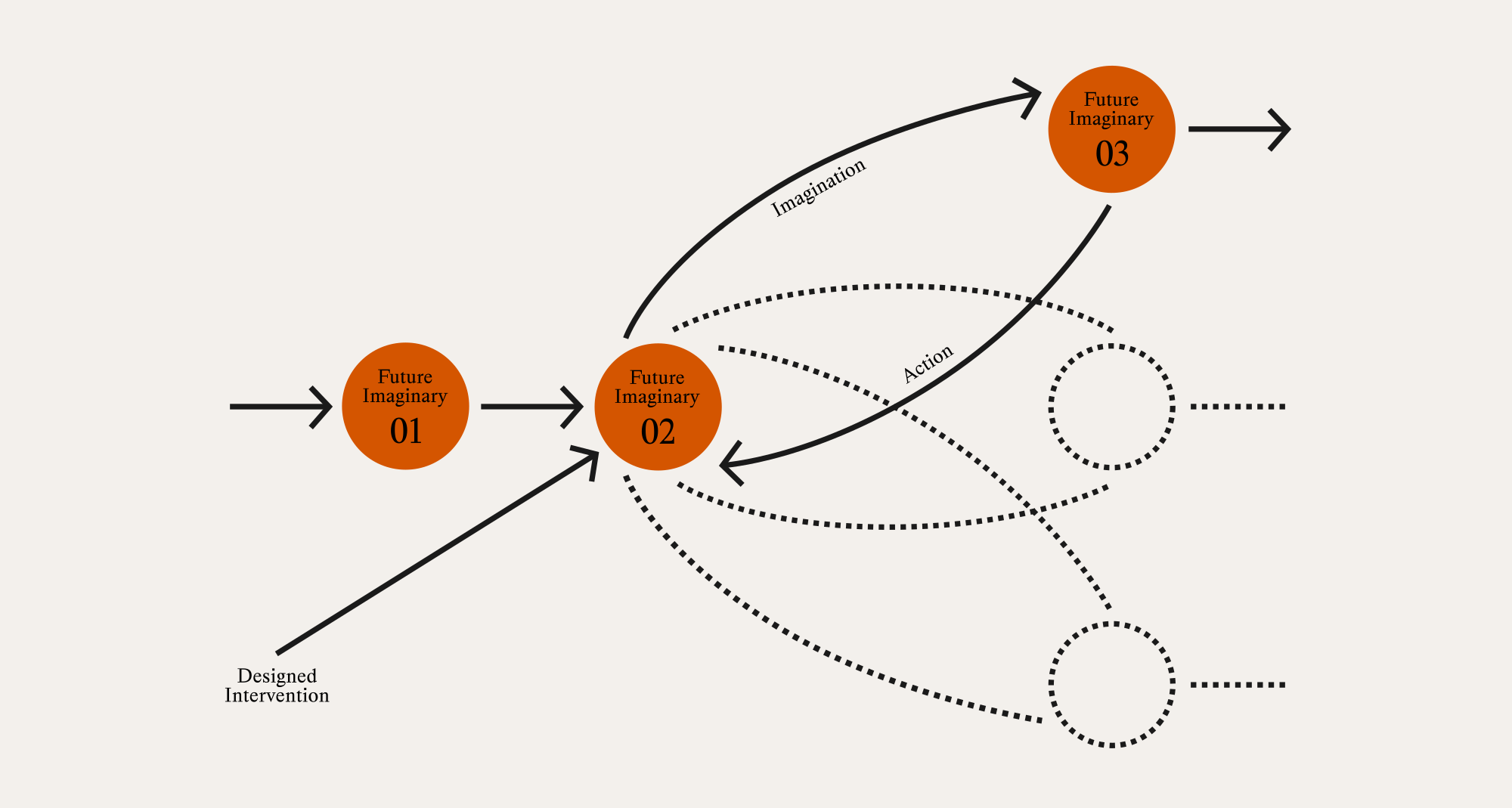

All individual and collective actors of a society contribute to the creation and distribution of future imaginaries. Organizations produce and distribute them through products and communications, individuals through informal communications, movie makers through narratives and politicians through speeches and decisions. For that reason, the following will also outline how to design interventions that transform existing future imaginaries, and therefore enable societal transformation processes towards more resilient and sustainable futures.

Social Change and Societal Transformation

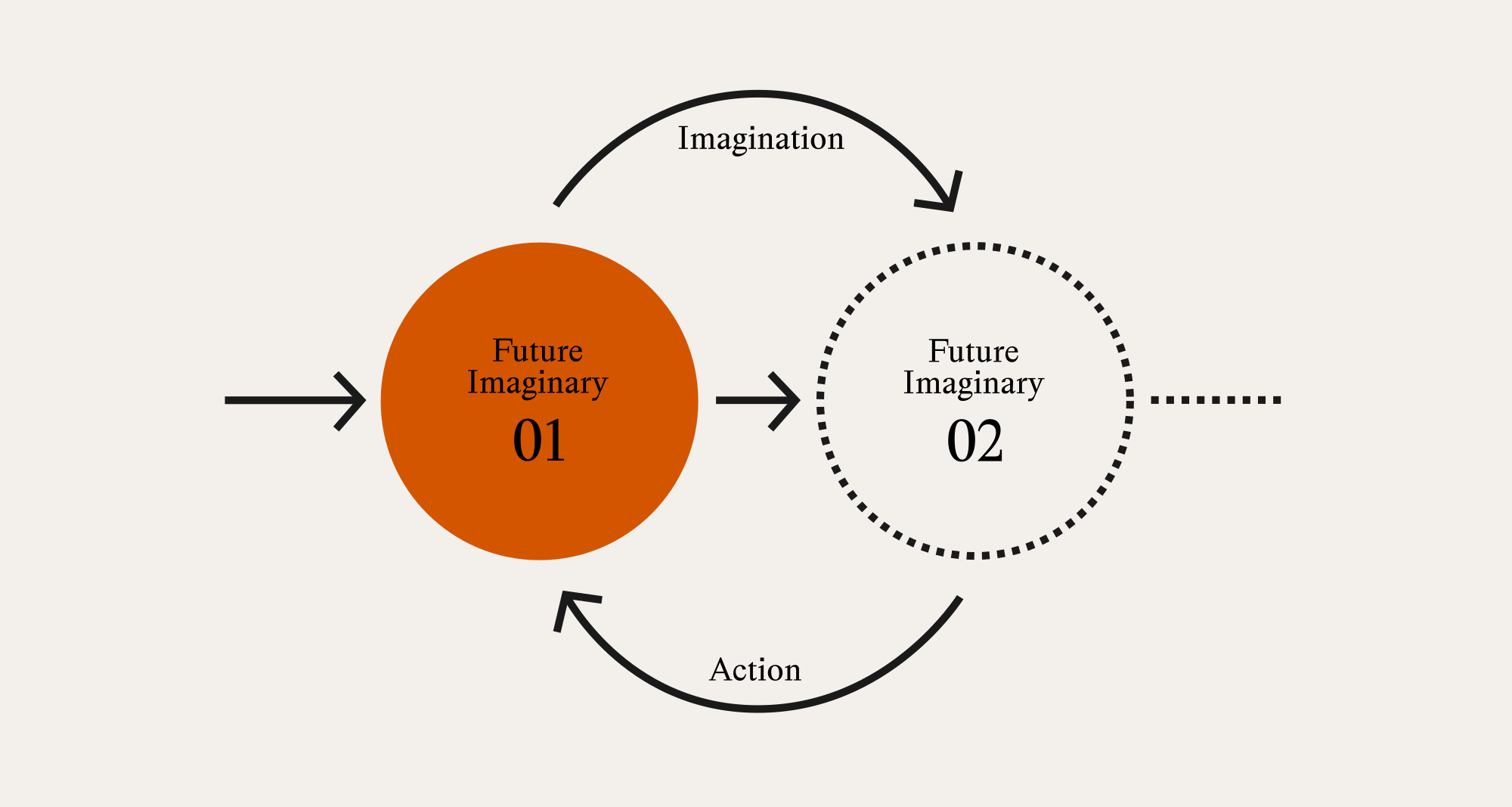

When a group of engineers develops a technology, when people trade a good through a prior defined currency or when youths create a movement to fight for their future. All these are social phenomena where humans act and interact with each other and the sum of these actions produces structures which in turn affect following actions and interactions (Schimank 2016). These interdependencies between actions and the formation of social structures define under which conditions and how humans interact with the natural environment in social-ecological systems. An economic system for example has social structures with roles and practices influenced by beliefs, norms, assumptions and worldviews. Such structures define how humans act within the structure and these actions form the further structural development of the economic system, which in turn defines the further actions of humans within it. These interdependencies between actions and structures create a repetitive loop that over a period of time becomes a social process (Esser 1999). When this process gets exposed to external influences each loop of the social process changes its state and the social process becomes social change. This could be a change in language, norms, social order, cultural practices or behavioral patterns. When for example an economic system that follows the idea of infinite growth gets exposed to the influences of sustainability science, social change could mean the emergence of an idea like green infinite growth.

Societal transformations are fundamental changes in a society that affect beliefs, norms and assumptions, but also technology, production, consumption, infrastructure and politics (Wittmayer & Hölscher 2017). These transformations change the operating systems of a society like law or political institutions, or societal subsystems like transportation or the economy. Societal transformations are non-linear because they change the direction in which a society develops. If a transformation is intentionally designed, it addresses normative questions and aims to create changes towards more desirable futures, for example towards more sustainable and resilient societies. Whether its about economy or transportation the operating systems of a society are human creations and therefore social phenomena that are shaped by actions and structures. In order to enable transformations on a societal scale, humans have to take action and actively intervene in social change.

Future Imaginations and Future Imaginaries

Whenever we make a plan, develop a strategy, dream about a different state of the world, formulate assumptions of what could happen tomorrow or discuss the consequences of an action, we imagine possible futures in the present (Grunwald 2009). These future imaginations are mental constructions represented through language by sharing, explaining and discussing our thoughts and assumptions. How we perceive the world emerges from the experiences we made in the world and these experiences are defined by the social environments in which we grew up (Gergen 2015). Thus, these experiences also define our imaginations about the future, and thereby enable and constrain them. This mental limit defines the field of action within which we navigate and move from the present into the future. In order to imagine alternative futures that are outside of our mental limit, we have to make experiences that expand these limits.

So far future imaginations have been outlined, but what are future imaginaries? And what is the difference between the two terms? The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor (2002) describes imaginaries as stories or narratives of how people imagine their social coexistence. But these kinds of imaginations aren't individual imaginations, they are shared by a large group of people or even a whole society, what makes common practices possible and enables a widely shared sense of legitimacy. On that basis, future imaginaries are imaginations about the future that are so common, widely shared and unquestioned within a society, that they guide the actions of large groups of people or a whole society towards a common direction. In that sense they are part of the social structures of societies and can be found in roles and practices. Often these future imaginaries emerge as future imaginations and then spread through informal and formal communication in visual, written or spoken language. Statements such as “artificial intelligence is the future” or “electric mobility is the future” are common representations of such future imaginaries.